Organization Structure Issues of Medieval Church

Organizational Confusion & Conflict

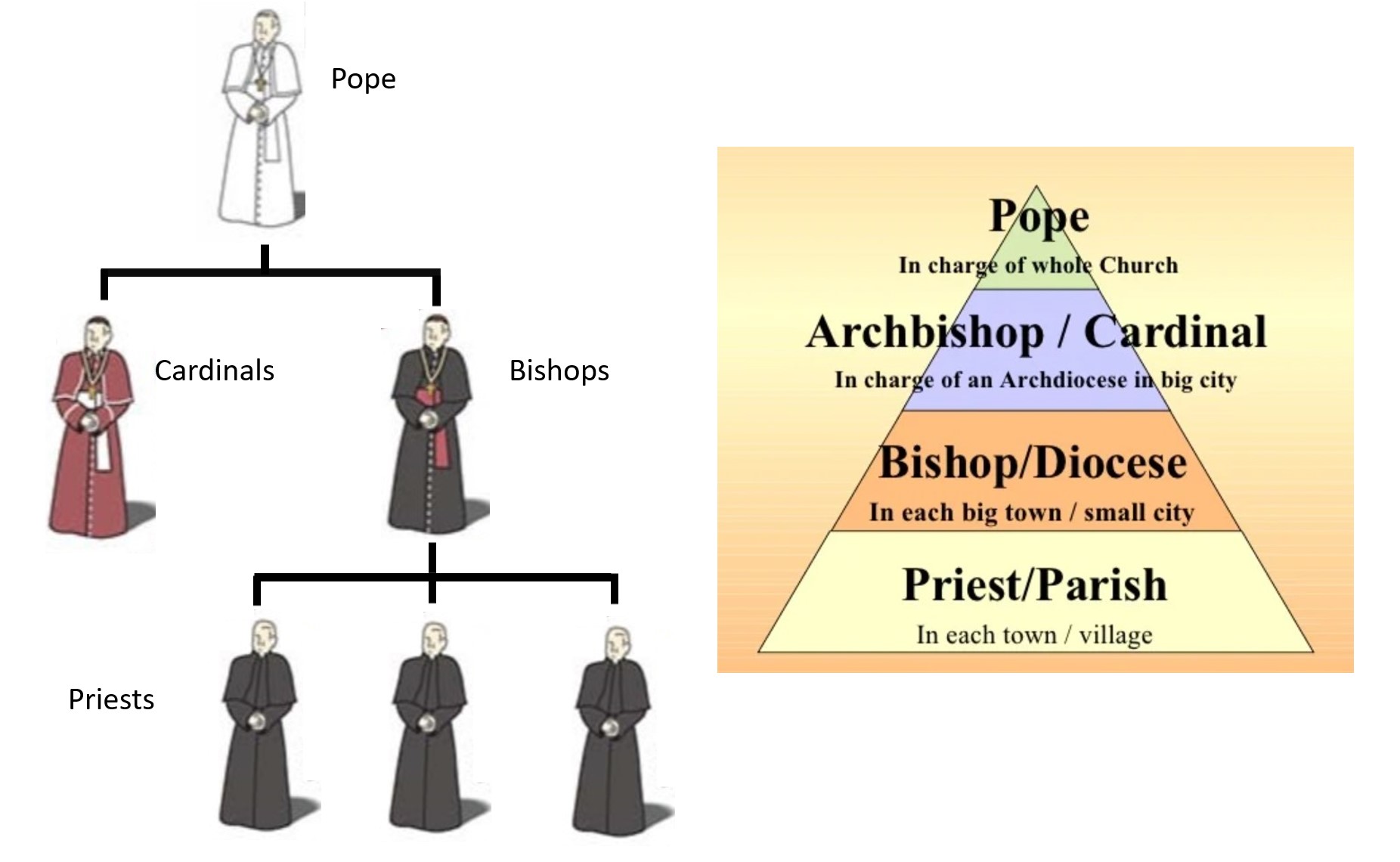

Centuries of accumulated ecclesiastical institutions, theological traditions, and religious practices added excessive, often conflicting layers of authority, creating a historical example of uncontrolled bureaucracy. The vastness and intricate hierarchy of the Church presented distinct challenges for decision-making. The sheer number of dioceses, bishops, and various religious orders scattered across Europe created a complex web of communication and authority.

Directives issued from Rome could take months, even years, to reach remote corners of the vast domain, often arriving filtered through layers of interpretation and local custom. This could lead to confusion and inconsistency, creating friction between central and local authorities.

Personal ambitions often led to power struggles and inertia. The internal power dynamics, with competing factions and vested interests, complicated decision-making and led to indecisiveness and delays in addressing pressing issues. Popes, theoretically holding supreme authority, faced resistance from powerful cardinals, bishops, and even monarchs. This intricate powerplay, while ensuring a measure of checks and balances, could also lead to indecisiveness and delays in addressing pressing issues. Ultimately, the Medieval Church’s structure presented significant hurdles in navigating the turbulent waters of religious and political life while increasing the pressure to change.

Conflicts with Secular Rulers

The Church and secular rulers contended for power most of the Middle Ages. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the so-called Papal Monarchy emerged. The popes of this era were powerful and confident, building and reforming institutions while also newly articulating the ideology of papal leadership. The Western Schism provided an opportunity for a host of challenges to papal rule.

Throughout the Middle Ages, the Pope claimed the right to depose the Catholic kings of Western Europe and tried to unsuccessfully to exercise it. By the end of the 16th century, the consolidation of power in the monarchy was complete, accompanied by the rise of professional standing armies, creation of professional bureaucracies, codification of state laws, and the acceptance of ideologies that justified the absolutist monarchy.