Schisms and Conciliarism

The Impact of Schisms on the Faithful

The “constitutional crisis” of the Western schism (1378–1415) raised questions about the ultimate locus of authority in the Church. The Schism was finally resolved at the Council of Constance (1414-1418). The Council deposed or accepted the resignation of the existing claimants and elected Pope Martin V in 1417, effectively ending the Schism and restoring papal authority in Rome. However, the schism and its repair led to the growth of conciliarism, a reform movement asserting that an ecumenical council has greater authority than the Pope, highlighting the shifting power dynamics within the Church.

The Western Schism significantly impacted the Church and broader society. It damaged the reputation of the papacy, undermining its spiritual and political authority. In its weakened political state, Church leaders were ill equipped to reconcile their teachings and actions in the emerging Renaissance.

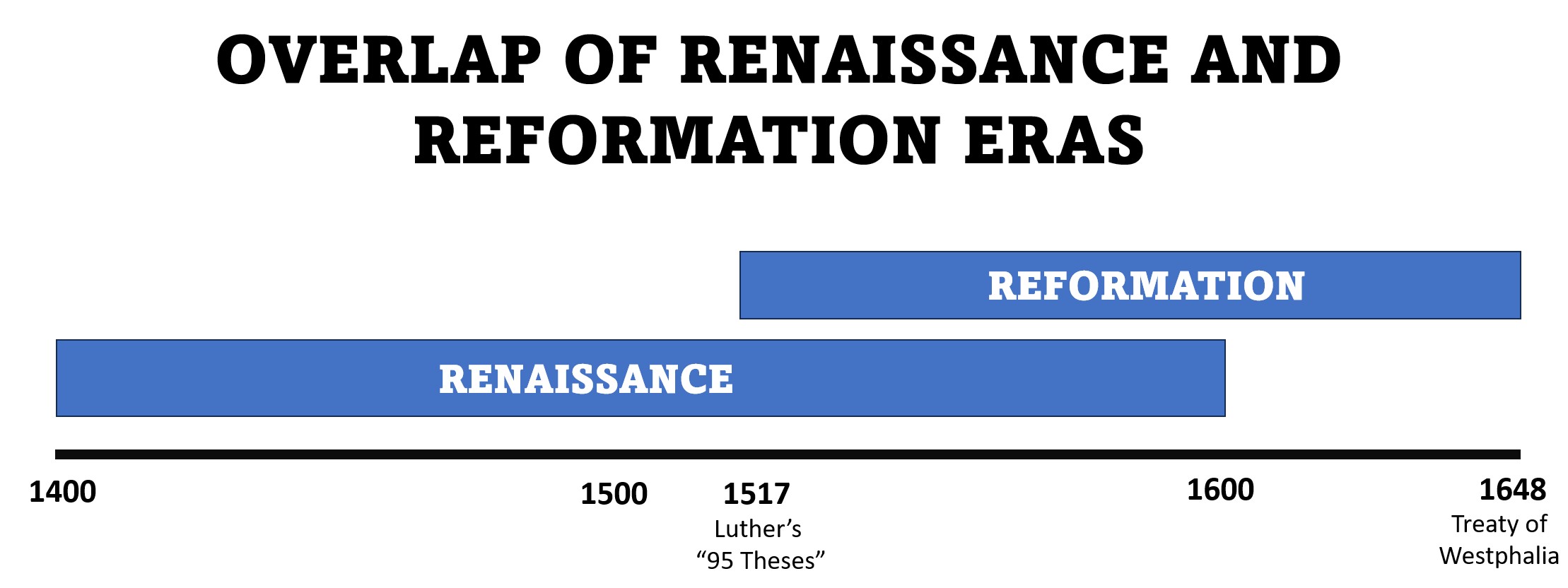

“Renaissance” comes from the French word for “rebirth.” An intense interest in and learning about classical antiquity – humanism – was “reborn” after the Middle Ages. Philosophers, theologians, and academics sought to revitalize their culture by integrating many of the values and ideals of the ancient world into their own times. The goal of Christian humanists was Christian renewal and a “return to the sources,” reexamining the text of the Bible by studying the original Hebrew and Greek writings and those of the early Greek and Latin Church Fathers. Their goal was to reform Christianity through philological erudition and moral education.

Christian philologists did not intend to attack the Church or Christianity, but to provide solid foundations for genuine reform. They envisioned a purified Christianity based on norms derived from scripture and the early Fathers, combined with a relatively optimistic view of human nature due to their immersion in other classical sources. They also believed that studying the original writings would identify practices deemed superstitious or harmful, justifications for deploring the ignorance of many Christians, and for criticizing sub-par clergy.

Erasmus (1466 - 1536)

The most influential Christian humanist – the prince of the humanists – was Erasmus whose “philosophy of Christ” sought the gradual moral improvement of Christendom through scholarly erudition and education. He viewed the central problems plaguing Christendom as ignorance and immorality, to be addressed through the scholarship and education of the “philosophy of Christ,” the inculcation of Christian virtue based on the Bible and the Church Fathers.

Erasmus wrote his Handbook of the Christian Soldier (1503) urging individual Christians to moral self-mastery of their passions and temptations. His Praise of Folly (1511) included the common devotional practices on the eve of the Reformation. Finally, he published a Greek

edition of the New Testament with his own Latin translation (1516).