Jewish Society One CE Continued

Jewish Sectarian Groups

Israel Community at Time of Christ

Since there were no official census at the time, Precise numbers are impossible to determine. Most estimates place the population of the combined regions of Judea, Samaria, and Galilee (roughly equivalent to modern Israel) somewhere between 500,000 and 1 million inhabitants living in villages and rural areas. Agriculture was the dominant economic activity.

Jerusalem was the largest city, likely holding tens of thousands of people. Other significant, but smaller, towns included Sepphoris, Caesarea Maritima, and Jericho. Population density was low by modern standards, though higher in the fertile regions like Galilee arid areas of Judea. Jerusalem, the site of the Temple, supported the largest population (est. 300,000 to 500,000) which could double during religious feast days.

Judaism was the by far the dominant religion of the land. It provided structure, community cohesion, and regulated most aspects of life. The Samaritans comprised a small but significant presence in the region of Samaria. Larger cities had pockets of Roman citizens and Hellenized (Greek-influenced) people, bringing exposure to non-Jewish religious practices.

As in most rural societies, social power was held by a small minority elite class who held positions of power in the Temple and the wealthy landowners. The groups were generally invested in the status quo and often collaborated with the Romans. The majority of the population were artisans, farmers, fishermen, and laborers. Slaves occupied the lowest rung on the social ladder.

The vast majority of the Jewish people in Judea as well as the Diaspora ascribed to some common principles, including the existence of a single God who acted in history, a single Temple in Jerusalem as the focal point of religious activity, and a law given by God to Moses to govern human behavior. Most Jews observed the Sabbath, gathering in synagogues to hear the law read. While the Temple and its ritual worship provided a unifying force in Jewish life, Judaism was slowly evolving into a religion focused on the Law and sacred scripture, a religion of “the book.”

As more Jews gained access to those sacred texts, a greater diversity of interpretation appeared. The development of Judaism into a religion, or way of life, encouraged a variety of opinions as to what that way required. Religious disputes led to sectarianism, with each group convinced that it alone observed the Law properly and was thus worthy of recognition as the true Israel. At the turn of the millennium, Jews generally fell into one of four sectarian groups: Sadducees, Pharisees, Essenes, and Zealots.

A fifth group – Christians – appeared in the first century CE. Godfearers were non-Jews who revered the Jewish God. Unlike “proselytes” who had made a full commitment to the requirements of Judaism, Godfearers expressed enough interest in Judaism to attend synagogue and possibly give alms but did not fully embrace the Law (Genesis-Deuteronomy). They were likely some of the earliest converts to the Christian faith.

According to Dr. Jospeh Fannin of the Dallas Theological Seminary, ” For the most part Christians were seen by their neighbors as superstitious, unwilling to participate in the Roman system, and as atheists. Though seen as guilty of crimes, they were usually not actively pursued and punished.”

Sadducees

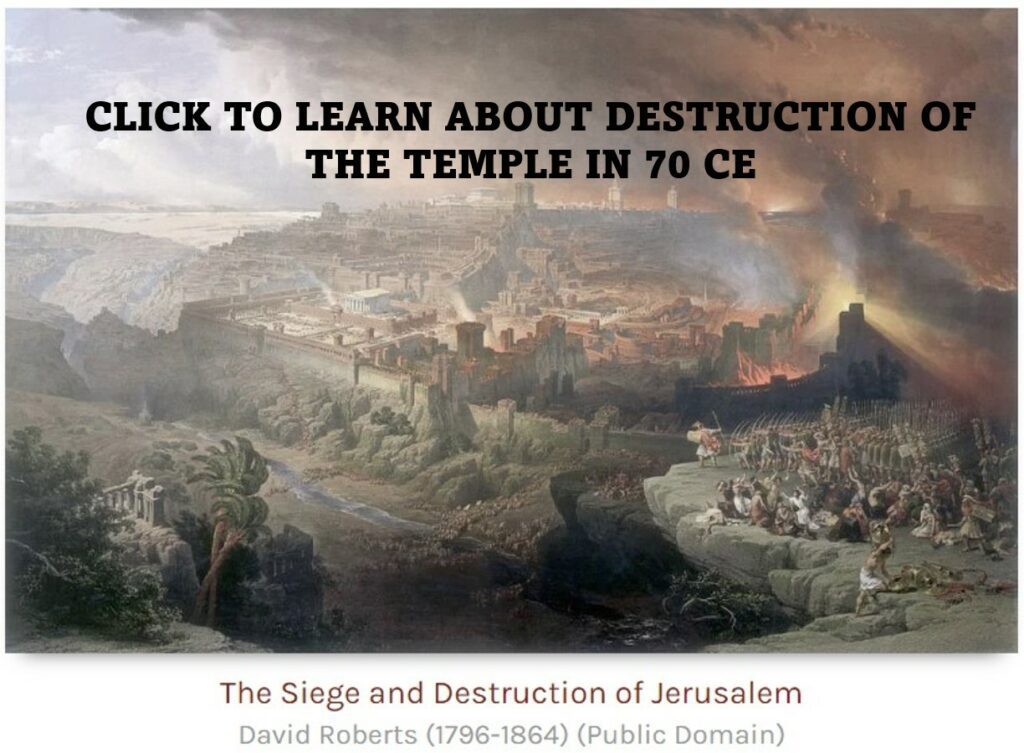

The Sadducees were a Jewish sect primarily comprising the priestly families and wealthy social elite closely tied to the Temple in Jerusalem, Members typically held major leadership roles, including that of the High Priest, thereby controlling Temple rituals and affairs. They disappeared following the Roman destruction of the Temple in 70 CE.

Sadducees stressed a strict adherence to the written Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible) and rejected the oral traditions embraced by other Jewish groups, such as the Pharisees. While they undoubtedly resented Roman occupation, the Sadducees adopted a pragmatic approach, preferring cooperation to open rebellion, which they likely considered futile and a threat to their own power. Maintaining the status quo enabled them to preserve their roles as Temple aristocracy and continue with their traditional religious practices under Roman rule.

The Sadducees did not believe in resurrection of the dead but believed in the traditional Jewish concept of She ol for those who had died. As the Talmud developed, Jewish theology reflects a diverse understanding of the afterlife and the resurrection of an earthly body.

Pharisees

The Pharisees represented a prominent religious and social sect within Jewish society in Judea, seeing themselves as scholars and experts in the Jewish Law (the Torah) and its oral traditions. They emphasized a strict adherence to the laws that governed ritual purity, dietary restrictions, Sabbath observance, and other aspects of daily life.

The Pharisees were considered a movement of the common people. Their interpretations of the law – beliefs in the resurrection of the dead, divine reward and punishment in the afterlife, and the existence of angels and spirits – sought to make Judaism accessible and applicable outside the Temple in Jerusalem and contrasted with the Sadducees.

The Pharisees held complex and often contrary views regarding the Roman occupiers. Like many other Jews, Pharisees resented the Roman occupation as an affront to God’s sovereignty and the Romans’ practices were often considered pagan and corrupt. Even so, they did not advocate for open rebellion, seeing it as futile and likely to result only in greater suffering for the Jewish people. Many Pharisees nurtured a deep hope for a divinely appointed Messiah, a figure who would overthrow their oppressors and restore Israel to its rightful place.

Essenes

The Essenes have gained fame in modern times as a result of the discovery of an extensive group of religious documents known as the Dead Sea Scrolls, which are commonly believed to be the Essenes’ library. They were a smaller but highly distinct sect within Judaism during the Roman occupation.

Essenes distanced themselves by living in communal, often ascetic, self-sufficient settlements. They placed a paramount emphasis on ritual purity and spiritual preparation, meticulously following a strict observance of Jewish Law. They also held deep apocalyptic beliefs, anticipating an imminent, divinely ordained battle between the forces of good and evil. They saw themselves as the righteous remnant who would be preserved through this cosmic struggle.

The Essenes equated the Romans with the forces of evil in their apocalyptic framework. Roman idolatrous practices and disregard for Jewish law were considered it a defilement of Jewish land and a direct affront to God’s sovereignty. However, Essenes did not advocate armed rebellion against Rome, rather choosing to withdraw into isolated closed communities to minimize interactions with other Jewish sects and their Roman occupiers.

Zealots

The Zealots represented a fervent, nationalistic movement within Jewish society in Judea during the period of Roman occupation. Their defining characteristic was an unshakeable commitment to direct and often violent resistance against Roman rule.

Zealots did not come from a single social class or group. Their ranks included commoners, former revolutionaries, and even those drawn from priestly circles. They were driven by a passionate religious conviction that Judea should be ruled only by God. Roman occupation was an intolerable violation of this belief and a desecration of their Holy Land.

Zealots believed that armed rebellion was the only righteous and effective way to expel the Romans and restore Jewish independence. They were known for assassinations, targeted raids, and acts of guerrilla warfare against Roman soldiers and their allies. Some Zealot factions eagerly awaited a warrior Messiah who would spearhead the liberation of Israel. Their hope in such a figure likely intensified their revolutionary fervor. While Jesus did not fulfill their expectations, the Romans crucified him as a rebel, a zealot and a pretender to the Judean throne (Matthew 27: 15-54).

(.