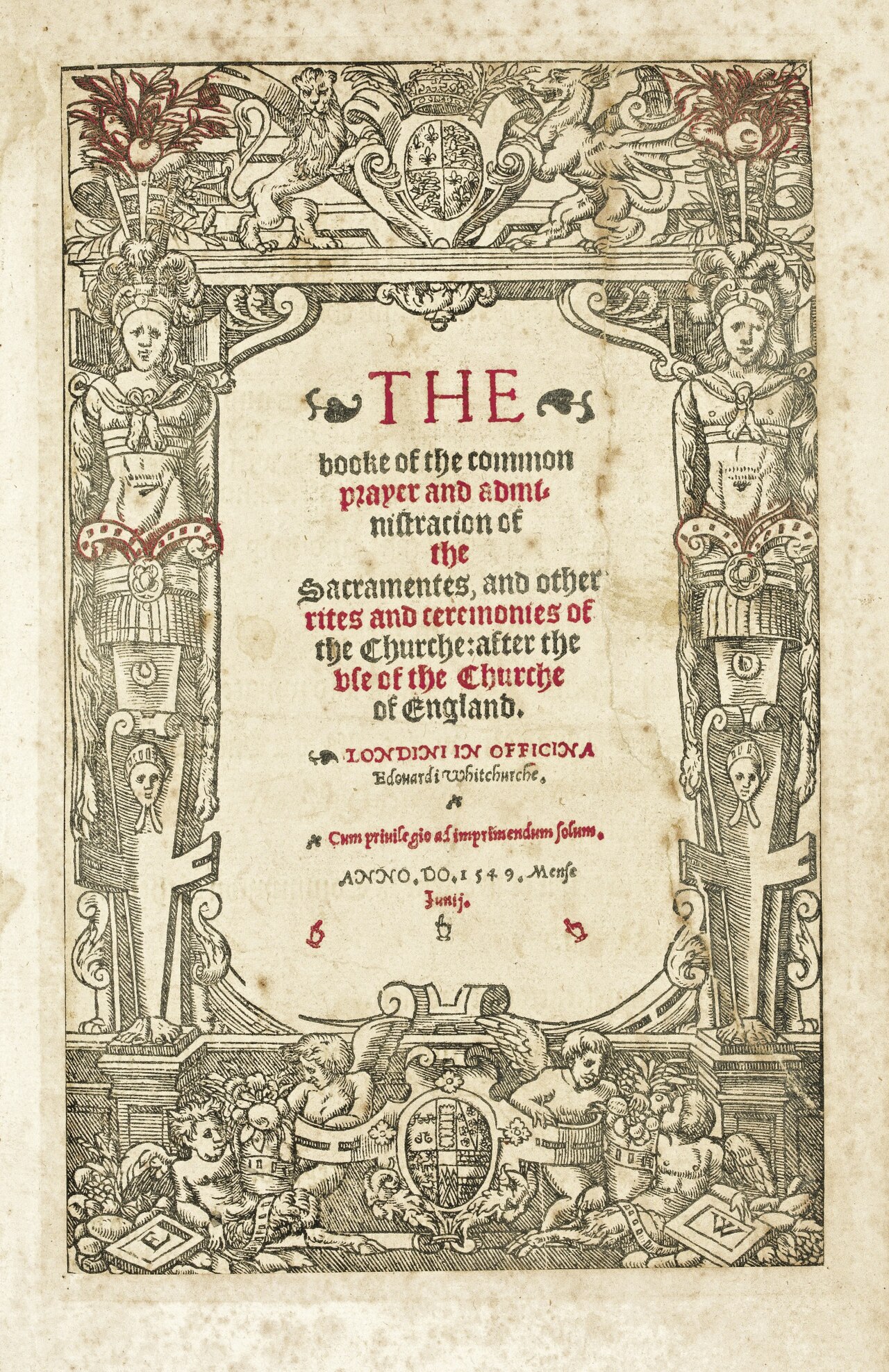

Book of Common Prayer 1549

The Genesis of the Book of Common Prayer 1549

Henry VIII believed that people did not responding to these church processions as they should, because “understode no parte of suche prayers or suffrages as were used to be songe and sayde”. Accordingly, the King decreed in June 1544, that there were to be “set forthe certayne godly prayers and suffrages in our natyve Englyshe tongue.” Archbishop Cranmer subsequently produced the first Litany in English, partly his own composition, and partly drawn from the Sarum (i. e., Salisbury) processional, from Luther’s Litany, and from the Greek Orthodox Litany.

The Litany was the forerunner of what was to become the 1549 Book of Common Prayer produced by Cranmer’s Committee of Thirteen -a group of Cranmer and twelve noted Bishops and theologians including:

- Nicholas Ridley, Bishop of Rochester,

- John Hooper, Bishop of Gloucester

- Richard Cox, Chancellor of Oxford University and later Bishop of Ely.

- Edward Wotton, Dean of Canterbury

- Edmund Bonner. Bishop of London

- Thomas Goodrich, Bishop of Worcester

- Hugh Latimer, Bishop of Ely

- Robert Aldrich.,

Readers should be aware that information regarding the identity and lives, and even the spelling of the names above may be incorrect. Nevertheless, records suggest that they debated theological nuances, reviewed drafts, and offered suggestions to the writing of the BCP. In addition, Cranmer is thought to have consulted other scholars and humanist reformers like Martin Bucer and Peter Martyr Vermigli to ensure the book aligned with ecclesiastical and political realities.

Comparison with Catholic Doctrine and Liturgies

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer was a groundbreaking document that attempted to navigate the middle ground between Catholicism and Protestantism. It retained familiar Catholic structures while introducing significant changes reflecting emerging Protestant ideas.

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer inherited a significant portion of its language from Catholic catechisms and liturgies, reflecting an era of transition and the delicate balance Cranmer sought between continuity and reform. Here’s a breakdown:

Familiar Structures:

- Latin Phrases: While shifting to English, the Prayer Book retained several familiar Latin phrases like “Kyrie eleison” and “Te Deum laudamus” for continuity and resonance with existing traditions.

- Order of the Service: The basic framework of the Mass, with elements like collects, epistles, gospels, and litanies, was preserved, providing a familiar structure for worship and easing the transition for clergy and laity accustomed to Catholic practices.

- Prayers and Hymns: Many prayers, including the Our Father, Hail Mary, and Nicene Creed, were incorporated with minor modifications, emphasizing shared Christian beliefs and maintaining a sense of connection to existing traditions.

Adaptations and Innovations:

- English Translations: The heart of the change lay in translating these elements into English, making them accessible to the lay majority and promoting vernacular engagement with religious practices.

- Protestant Theology: Cranmer subtly infused Protestant theological ideas, reinterpreting certain prayers and emphasizing concepts like justification by faith and scripture as the source of authority.

- Simplified Rites: Some Catholic rituals were simplified or omitted, reflecting the Protestant rejection of complex ceremonies and their desire for direct communication with God.

The 1549 Book of Common Prayer drew heavily on the familiar language and structures of Catholic traditions, providing a sense of continuity and stability during a period of religious change. However, it also incorporated essential Protestant ideas and innovations, marking a significant step towards a new identity for the Church of England and shaping the course of the English Reformation.

The Book of Common Prayer included the Apostles’ Creed and the Nicene Creed, central tenets of Catholic doctrine. These affirmations of faith served as a foundation for Christian belief and emphasized core doctrines like the Trinity and the Incarnation. The original Book of Common Prayer continued to recognize the seven sacraments traditionally practiced in the Catholic Church – Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Penance, Anointing of the Sick, Holy Orders, and Matrimony. While Cranmer’s views on the Eucharist evolved to a more Protestant understanding, he continued to acknowledge its importance as a sacrament.

While the new Book of Common Prayer firmly established the monarch (Edward VI at the time) as Supreme Head of the Church of England, the basic structure of the Catholic Mass, including kyries, collects, epistles, gospels, and prayers, was continued to provide a familiar framework for worship. However, they were adapted to a vernacular English service for increased participation and understanding by the laity.

The veneration of saints was deemphasized (including the removal of certain saints and pilgrimages) to place emphasis on direct prayer to God and a more scriptural focus (a Protestant position). Finally, prayers for the dead in purgatory was abolished, focusing on prayers for the living and emphasizing God’s grace and forgiveness.

Additional Comments and Analyses of English Prayer Book Changes

Over the past 500 years, there have been numerous changes in the BCP reflecting the social, political, and theological pressures at the time. there has always been a battle between orthodoxy and heresy, and it continues today. For those interested in specific details of the amendments, I recommend reading the following:

- The First Prayer Book of 1549 essay by the Reverend J. Robert Wright

- Archbishop Cranmer’s Immortal Bequest: The Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England: An Evangelistic Liturgy by Samuel Leuenberger

- A Short History of the Book of Common Prayer by Reverend William Reed Huntington

- Everyman’s History of the Prayer Book by Percy Dearmer, D. D.

Changes in Catholic practices and 1549 Book of Common Prayer

The 1549 Church of England Book of Common Prayer and Catholic doctrine and liturgies in the 1500s underwent significant changes as a result of the English Reformation and the establishment of the Church of England as a separate entity from the Roman Catholic Church. Here are some key differences between the two:

- Authority:

- Catholic Doctrine (1500s): The Roman Catholic Church believed in the supreme authority of the Pope and the Magisterium.

- 1549 Book of Common Prayer: The Church of England rejected the authority of the Pope and established the English monarch – initially Henry VIII and later monarchs, as the head of the church in England.

- Language of Worship:

- Catholic Doctrine (1500s): The Roman Catholic Mass and liturgy were conducted in Latin, which was not understood by the common people.

- 1549 Book of Common Prayer: The Church of England introduced the use of English in the liturgy, making it more accessible to the laity.

- Eucharist/Communion:

- Catholic Doctrine (1500s): The Catholic Church believed in transubstantiation, the idea that the bread and wine used in the Eucharist actually become the body and blood of Christ.

- 1549 Book of Common Prayer: The Church of England held a more symbolic view of the Eucharist, rejecting the idea of transubstantiation.

- Clergy Marriage:

- Catholic Doctrine (1500s): Priests in the Roman Catholic Church were required to be celibate and could not marry.

- 1549 Book of Common Prayer: The Church of England allowed clergy, including priests, to marry.

- Religious Art and Icons:

- Catholic Doctrine (1500s): The Catholic Church was known for its use of religious art, icons, and statues in worship.

- 1549 Book of Common Prayer: The Church of England discouraged the use of religious art and icons in worship, leaning towards a more austere form of worship.

- Liturgical Structure:

- Catholic Doctrine (1500s): The Roman Catholic Mass had a more complex and ritualistic liturgical structure.

- 1549 Book of Common Prayer: The Church of England introduced a simpler and more streamlined liturgical structure in the Book of Common Prayer.

- Intercession of Saints:

- Catholic Doctrine (1500s): The Catholic Church believed in the intercession of saints and the veneration of relics.

- 1549 Book of Common Prayer: The Church of England rejected the intercession of saints and the veneration of relics, emphasizing a more direct relationship with God.

These are some of the key differences between the 1549 Church of England Book of Common Prayer and Catholic doctrine and liturgies in the 1500s. The English Reformation brought about a divergence in theology, liturgy, and practice between the two religious traditions.

Religious Wars After Reformation

Religious Wars After Reformation

Europe in the 16th century became a bloody battleground for the soul, scarred by a series of religious wars ignited by the Protestant Reformation. Luther’s fiery challenge to papal authority sparked a theological tinderbox. Catholic monarchs clashed with rebellious Protestant nobles, fueled by a potent mix of political ambition, religious fervor, and territorial disputes. France, Germany, and the Netherlands erupted in brutal conflicts, marked by massacres like St. Bartholomew’s Day and sieges like Leiden. Over 10 million died in France and Germany alone.