Lesson Three: Messenger and Message

The Message and Teaching of Jesus

Jesus of Nazareth, a Jewish teacher and healer from the region of Galilee, is indisputably one of the most influential figures in human history. His life, teachings, and eventual death spawned the faith known as Christianity, which now has adherents numbering in the billions worldwide. He was not only a teacher of ethical principles, but an evangelist. He passionately shared his message of the Kingdom of God, calling on people to repent, embrace radical love, and embody a life transformed by God’s grace.

Long before the appearance of a written account of his life and teachings, Jesus preached the “Good News” to crowds gathered on hillsides, by the seashore, and at religious festivals. He used parables, vivid stories designed to convey spiritual truths and challenge his listeners. Considered a Jewish rabbi, Jesus taught in synagogues, interpreting Old Testament scripture and debating religious matters with other teachers. He also interacted with individuals seeking healing, guidance, or theological discussion (John 4:7-42; John 5:1-15; Matthew 9:16-30; Mark 5:1-43). These personal encounters were often profound moments of transformation.

The central theme of Jesus’s teachings was the Kingdom of God. His vision was not a literal, earthly kingdom but a spiritual transformation wherein God’s love, justice, and mercy would reign over the hearts of individuals and, ultimately, society. Jesus emphasized the following principles:

-

- Unconditional love: Jesus advocated for boundless love towards God, oneself, and even one’s enemies. This radical love was the foundation of a true relationship with God and the way to bring about his Kingdom.

- Forgiveness: Jesus emphasized forgiveness both as a gift from God and as the responsibility of his followers. Forgiveness, he taught, breaks cycles of hatred and retribution. The sacraments of baptism and holy communion are specifically identified in the Gospels and Acts for Christians.

- Humility and service: Jesus frequently overturned social norms by favoring the meek, the poor, and the marginalized. He exemplified a servant-leader, washing his disciples’ feet as a sign of humility and demonstrating that true greatness comes from serving others.

- Inner transformation: Jesus taught that the Kingdom of God begins with a change of heart, not simply adherence to external laws. This involved cultivating virtues like compassion, honesty, and selflessness.

Jesus’s ministry and his challenging messages attracted the ire of the political and religious authorities of his day. His presence and proclamations were especially troublesome to Jewish authorities. Historically, their experiences with God relied exclusively on prophesies and visions through God’s chosen messengers like Abraham and Moses. Jesus was the living revelation of God’s word; He offered personal salvation to everyone while Jews expected a restoration of the Davidic Kingdom. His message transcended ethnic and national boundaries, being offered to all, Jew and Gentile.

He was eventually arrested, tried, and crucified by the Romans at the insistence of the Jewish authorities. Three days after his death, Jesus rose from the dead. While the resurrection is central to Christianity and is understood as a victory over sin and death, it was a stumbling block for many Jews. The idea of a Messiah dying a shameful death didn’t align with expectations of a victorious political leader.

Christians believe his death was a sacrifice for the sins of humanity. His resurrection is validation of his messianic claims and a sign of God’s triumph over sin and death, leading to the promise of eternal life for believers. Judaism emphasizes the written Torah and its interpretation through rabbinic tradition. While Jesus also engaged in the oral transmission of teachings through parables and sermons, the early Christian movement trusted the oral witness of his disciples and the spread of his message before the emergence of written Gospels.

The Beginning of His Ministry

Biblical Scholars generally agree that Jesus’ public ministry began after his baptism by John the Baptist at the age of 29-30 years (Luke 3:23). His ministry lasted approximately one to three years until his crucifixion in Jerusalem between 30 and 36 BCE; the Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) suggest a shorter timeframe, while the Gospel of John hints at three Passovers during Jesus’ ministry. Christians believe his coming was prophesied multiple times in the Old Testament and fulfilled with his Divine birth.

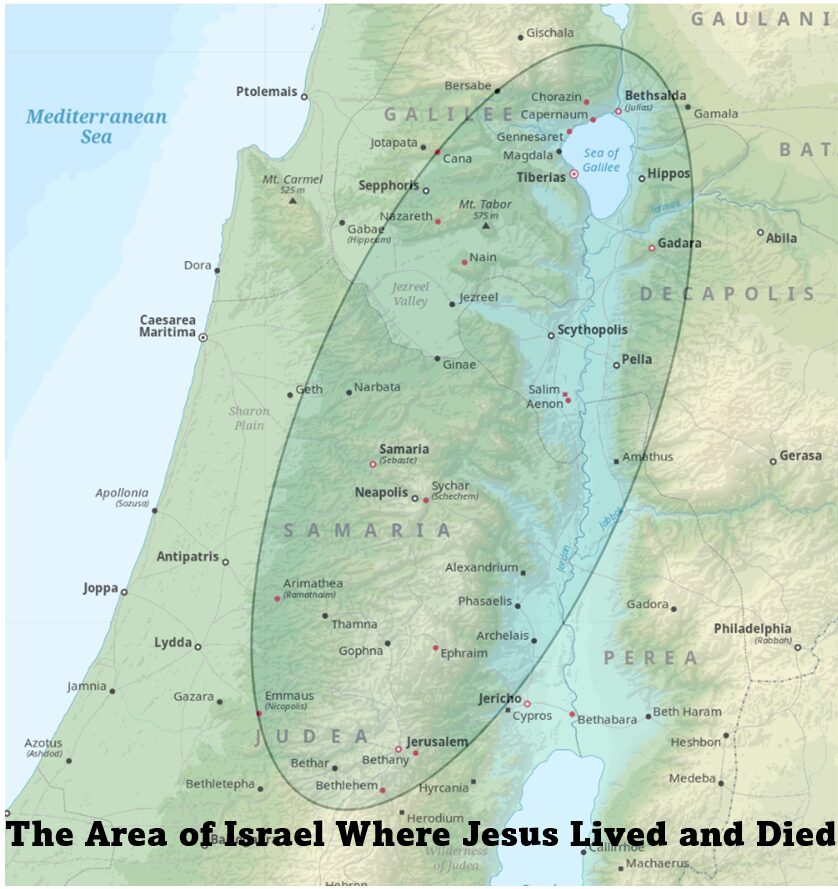

The geographical area of Jesus’ ministry was relatively small, though exact boundaries are difficult to identify. For example, the passages in the Gospels mentioning his family’s flight to Egypt to escape Herod’s Slaughter of the Innocents (Matthew 2:13-23) do not identify specific towns or landmarks and is not included on the adjacent map. His ministry was generally bounded on the north by the Sea of Galilee and 180 kilometers to the south by Jerusalem, a territory approximately to the size of Rhode Island or half the size of California’s Yosemite Park in the United States.

According to the Gospels, Jesus and his Apostles crisscrossed the territory on foot spreading the Good News, returning to Capernaum as a home base in Galilee. They made several trips to Jerusalem during Jesus’ ministry before his death (the key regions and some specific locations where Jesus is recorded to have preached, taught, and performed miracles).

The Devil, Demons & Hell

Long before Christian theology formalized the concept of the Devil, ancient civilizations like the Zoroastrians and Egyptians grappled with ideas of good vs. evil, often personifying evil as a disruptive force rather than an outright malevolence. For instance, Zoroastrianism posited a cosmic dualism between Ahura Mazda (good) and Angra Mainyu (evil).

In Judaism, the figure known as “Satan” does not initially embody pure evil but serves as an adversary or accuser, possibly reflecting a prosecutorial role within the divine council, as seen in the Book of Job. Over time, particularly during the Second Temple period, this character evolves towards the more autonomous adversary known in Christianity.

Christianity significantly develops this figure, portraying Satan as a fallen angel—Lucifer—who rebels against God due to pride, as described in Ezekiel 28:11-19. This narrative introduces a more personalized and enduring evil opposing God and humanity. The term “Satan” appears variously across the biblical texts, symbolizing obstruction or opposition. By the New Testament period, Satan is depicted as a distinct cosmic evil, involved in direct opposition to Jesus, as illustrated during the temptations in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1-11, Luke 4:1-13).

Scholars like Henry Ansgar Kelly emphasize that earlier Jewish texts do not depict Satan as inherently evil but rather as fulfilling a role within God’s plans. This interpretation is supported by instances where Satan acts upon divine sanction to test or accuse humans.

Role of Demons and Their Confrontation

- Biblical Accounts: Demons in the New Testament are often portrayed as beings under Satan’s command, causing physical and spiritual affliction. Jesus and His Apostles frequently confront and exorcise these demons, demonstrating divine authority and the inbreaking of God’s kingdom (Mark 1:23-26; Matthew 17:14-20).

- Apostolic Authority: The Apostles, empowered by Jesus, engage in numerous acts of exorcism, affirming their role in the divine mission and the reality of spiritual warfare, which was a prevalent concept in early Christian communities (Acts 16:16-18).

While traditional depictions of Hell and demons persist, many contemporary theologians and denominations, including the Episcopal Church, prefer to interpret these concepts symbolically. Hell is seen less as a punitive fire and more as a metaphor for existential separation from God.

Hell: Evolution of the Concept

Various ancient cultures held beliefs in an afterlife that included realms of punishment or moral reckoning. Over time, influenced by interactions with neighboring cultures and evolving theological reflections, these views gradually shaped the Christian concept of Hell as a place of eternal punishment.

In Christian theology, Hell is articulated as a fiery realm where sinners face eternal damnation, distinct from earlier, more nuanced underworlds of other religions. Jesus’ teachings in the New Testament introduce Hell as a definitive consequence for moral failure (e.g., Matthew 25:45-46).

Across Christianity, views on Hell vary from its existence as a literal place of fire (traditionalist view) to metaphorical interpretations where Hell represents a state of separation from God’s grace (modern perspectives).

The Episcopal Church approaches the concept of the Devil , Demons, and Hell with nuance, viewing these as symbolic of broader spiritual and moral struggles rather than literal beings or places. This aligns with broader Christian shifts towards understanding evil and redemption in contextually relevant and psychologically profound ways. In summary, the evolution of the concepts of the Devil, Hell, and demons reflects a complex interplay of scriptural interpretation, cultural interactions, and theological speculation. Modern Christianity, including perspectives from theologians like N.T. Wright and practices within the Episcopal Church, often emphasizes a metaphorical understanding of these elements, focusing on their allegorical rather than literal significance.